January 9th, 1349: Basel Massacre - Jews Burned Alive

On this ominous day in 1349, the Basel Massacre unfolded, targeting the city's Jewish population as an ignorant attempt to eradicate the Black Plague.

On the fateful day of January 9th, 1349, in Basel, Switzerland, a chilling scene unfolded—one that not only echoes the darkest side of human nature but also serves as a sad reminder of history's repetitive dance with fear and prejudice.

The Black Death, a merciless plague, was ravaging Europe, leaving a trail of death and despair.

The Medieval times were an era marked not only by disease but also by extreme ignorance about their origins and transmission.

This lack of understanding bred superstition, and superstition birthed scapegoats.

The Black Plague

In the 14th century, as the Black Death ravaged Europe, a blend of fear, ignorance, and religious fervor gave rise to a host of superstitious practices and beliefs.

These practices were not mere eccentricities; they were desperate attempts to make sense of and combat an unseen, deadly enemy.

The Beaked Mask

Among the most striking of these practices were the plague doctor costumes.

These doctors wore beak-like masks, which were filled with aromatic substances like herbs and spices to mask the stench of rotting human flesh.

The common belief was also that these strong scents could ward off the disease, as it was widely thought by doctors of the time, that the plague was spread through miasma, or "bad air."

The beaked mask, thus, became a symbol of both the fear of the unknown and the desperate human attempt to find safety in superstition.

The Evil Whip

Additionally, some turned to flagellation, whipping themselves or others in public displays of penance.

They believed that the plague was a punishment from God, and by inflicting pain upon themselves, they hoped to appease divine wrath.

This practice, rooted deeply in religious belief, showcased the intersection of fear and faith, where physical suffering was seen as a pathway to spiritual salvation.

The Wax Suits

The use of body suits, often wax-coated, was another method employed by plague doctors.

These suits were designed to cover every inch of the body, creating a barrier between the doctor and the diseased.

This practice, albeit rudimentary by modern standards, was a testament to the human instinct to innovate in the face of existential threats.

These practices, while seemingly bizarre to the modern eye, were grounded in the religious and scientific understanding of the time.

They were the 14th-century equivalent of a desperate scramble for control, a tangible response to an intangible terror.

Jewish Extermination

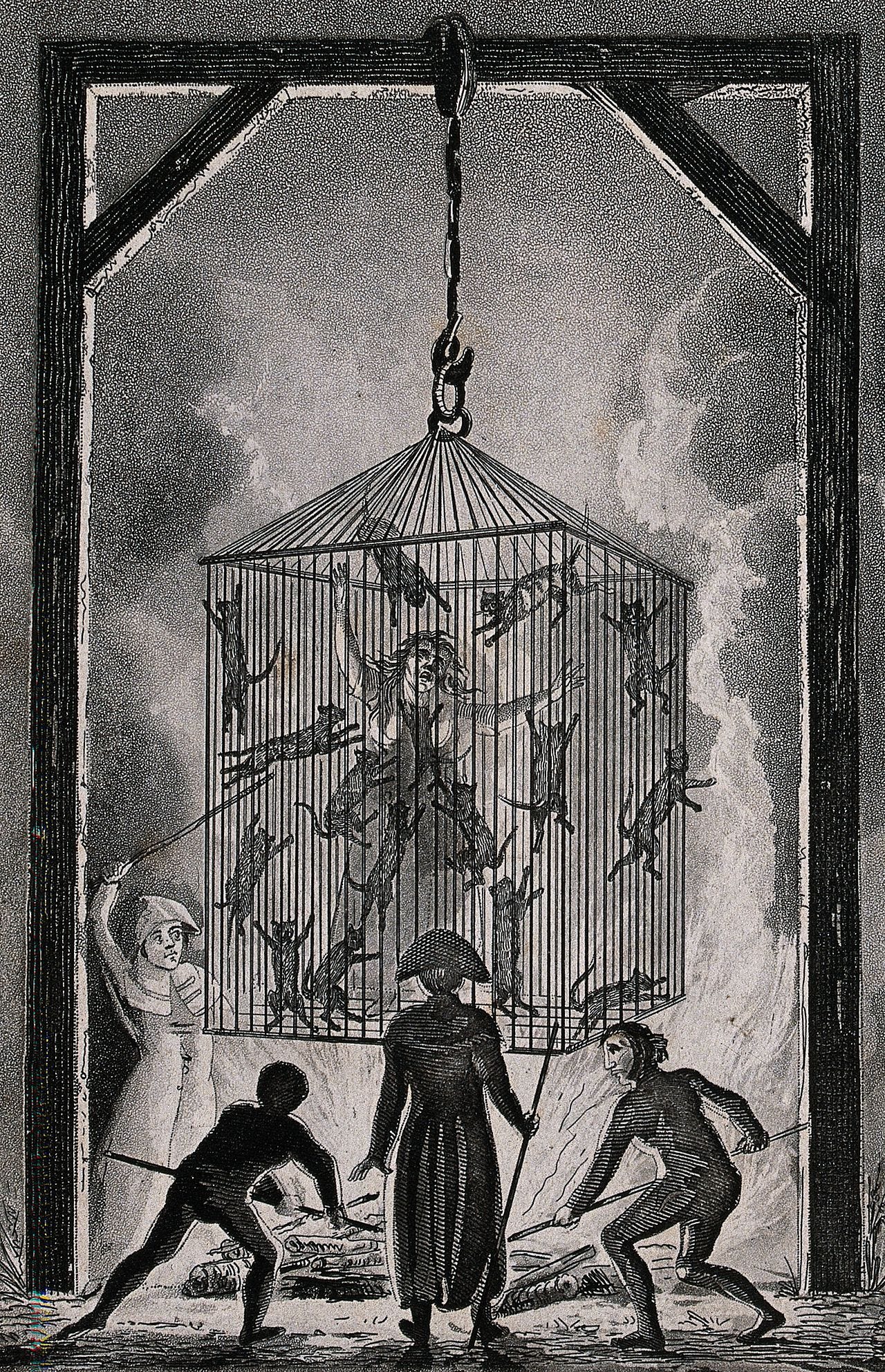

In Basel, this manifested in a horrific and unfathomable act against the Jewish community, falsely accused of causing the plague.

The setting of this narrative is as important as the characters involved.

Basel, a medieval city, was shrouded in the darkness of the plague.

The air was thick with fear, a breeding ground for irrational beliefs.

The Jewish Community

The Jewish community, an integral part of the city’s culture, found themselves tragically at the epicenter of this fear.

They were neighbors, traders, friends, and yet, when the plague’s shadow loomed large, they were seen as the other, the cause, the problem.

Amidst this, I see an individual, a Jewish man, whose name history has forgotten but whose story embodies the personal tragedy and collective hysteria of those times.

He stands, a father, a husband, perhaps a merchant, suddenly stripped of his identity, seen not as a fellow human but as a harbinger of death.

His bewilderment, his fear, and his profound sense of betrayal are felt today.

Barbarism Human Trait

This story isn't just about the physical act of violence that unfolded on that January day; it's also a window into the psychological turmoil experienced by both the persecuted and the persecutors.

What drove ordinary citizens to such an act of barbarism?

Fear, certainly.

Ignorance, undoubtedly.

But beneath these, a deeper, more unsettling human trait lurks – the need to find order in chaos, even if it means creating monsters out of our neighbors.

The Jewish population of Basel, rounded up, faced a fate that sends shivers down the spine.

A prelude to the holocaust to come 600 years later.

The Jews were incinerated, a brutal attempt to cleanse the city of what was believed to be the source of its suffering.

It’s a moment that starkly showcases the absurdity of certainty.

How could they be so sure the Jews caused the plague, the wrath from God?

And yet, they were so sure, so willing to burn fellow humans to try and prove it.

This wasn’t just a moment of physical destruction but also an annihilation of trust, humanity, and coexistence.

Reflecting on this from a modern perspective, it’s easy to cast judgment, to see this as a relic of a less enlightened time.

I am reminded of something Carl Sagan once wrote in Demon-Haunted World when he said:

“We are all flawed and creatures of our times. Is it fair to judge us by the unknown standards of the future? Some of the habits of our age will doubtless be considered barbaric by later generations…” —Carl Sagan

Scapegoating

Yet, isn’t this pattern of fear and scapegoating something we still witness today?

Aren’t there moments when society, driven by fear, clings to false certainties, creating dichotomies of us vs. them?

The historical context is critical here.

The 14th century was a time of limited scientific understanding.

The Black Death was a mystery, a seemingly incurable scourge from the heavens.

In such times, humanity often turns to superstition.

Smokescreen

The Jewish community’s persecution was not an isolated incident; it was part of a broader pattern of anti-Semitic violence in Europe, fueled by religious intolerance and social envy.

The Black Death, in its terrifying sweep across Europe, was more than a mere biological catastrophe; it served as a pretext for a darker, more insidious human drama.

In Basel, and indeed across much of the continent, this pandemic became a smokescreen, a convenient excuse to assert dominance over those deemed 'other'.

The Jewish community, with their distinct traditions and beliefs, became the unwilling actors in this tragedy, their otherness magnified into a threat, an easy target in a time of universal fear and uncertainty.

Resilience

This historical event, however, isn't solely a chronicle of the darkness that lurks within the human spirit.

It's also an incredible testament to resilience, to the unyielding strength of the human will.

The Jewish community, facing a horror that is hard to fathom, continued to persevere.

In Basel and beyond, they clung to their faith and identity, a beacon of light in an era shrouded in darkness.

Their story is one of enduring spirit, a reminder that even in the face of relentless persecution, the human spirit can, and often does, triumph.

The Real Cause

The Black Death, a scourge that overshadowed the 14th century, was eventually demystified through scientific inquiry, yet not before centuries of fear, superstition, and tragic misinterpretation.

It was only in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that the true cause of this relentless pandemic was unveiled.

In 1894, French biologist Alexandre Yersin identified the bacterium Yersinia pestis, revolutionizing our understanding of this and other infectious diseases.

For centuries, the Black Plague's primary vectors, fleas carried by rats, remained an unseen and deadly force.

Cats and Witches

Yet, there existed a natural deterrent to these plague carriers: cats.

Coincidentally, households with cats often had fewer rats and subsequently lower incidences of the plague.

This correlation, however, remained unrecognized in medieval times.

Instead of being seen as protectors against the disease, cats, and by extension, their owners, were ensnared in a web of superstition and fear.

In an era where the inexplicable was often attributed to witchcraft, those who kept cats were sometimes viewed with suspicion.

The natural predation of cats on rats, which could have been a critical observation, was overlooked.

Instead, households spared from the plague were accused of witchcraft.

Cats, often companions of those branded as witches, were vilified, seen as malevolent beings in league with dark forces.

The burning of witches and their feline companions became another grim chapter in the history of the Black Death, a chapter marked by fear overshadowing reason.

The absurdity of this situation is stark.

The Devil Helped?

While cries for divine intervention went seemingly unanswered, it appeared, in a tragic twist of irony, that those accused of witchcraft—essentially, cat owners—had their 'prayers' answered by darker forces.

This misconception reinforced the false narrative that while God turned a blind eye because the cursed Jew, the Devil, ironically swooped in and lent a helping hand.

To reconcile the notion of the Devil assisting instead of God, they resorted to burning alleged 'witches' and pushed the belief that the Jews were responsible for God's indifference.

The reality, of course, was far more prosaic: cats were simply following their natural instincts, oblivious to the human drama unfolding around them.

The eradication of the plague as a widespread threat was not immediate but a gradual process, involving scientific breakthroughs, public health policies, and improved sanitation.

Science Saves Lives

The discovery of Yersinia pestis shifted the narrative from one steeped in superstition to a more scientific understanding of disease transmission.

Science emerged as a savior, not only in combating the disease but also in gradually dispelling the layers of fear and superstition that had led to such tragic misinterpretations and acts of barbarism.

This history serves as a sad reminder of the dangers of misinterpreting natural phenomena through the lens of superstition and fear.

The events underscore the importance of scientific understanding in not only addressing public health crises but also in preventing the societal and moral crises that can arise from ignorance and unfounded fears.

The story of the Black Death, the cats, and the so-called witches is a testament to the complexity of human belief and the sometimes tragic consequences of our misunderstandings.

Homo Eugenics

As I look deeper into this history, a realization emerges about the depths of human fear and the lengths to which it can drive us.

The events in Basel illustrate a chilling truth: the line between civilization and barbaric behavior is indeed perilously thin.

This brings to mind a broader, more existential contemplation.

When we look back at our ancient past, at the survival of Homo sapiens over other hominid species, questions arise that are as unsettling as they are extreme.

Why did Homo sapiens prevail where others did not?

Do the scars of our recent history offer a glimpse into our ancient past?

There's a haunting possibility that the drive for dominance, the urge for homogeneity, might be deeply ingrained in our species.

Could it be that our history, both ancient and recent, is riddled with a tendency towards eugenics, a subconscious push for a singular, dominant species?

And in this pursuit, have we, as a species, repeatedly turned to the grim solution of extermination when faced with difference and diversity?

This line of thought, while speculative, serves as a reminder of the importance of historical awareness and self-reflection.

It highlights the need to recognize and confront our prejudices and fears.

The words of philosopher George Santayana echo loudly in this light:

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

—George Santayana

This statement isn't merely a reflection on a horrific event in history; it's a stark warning, a call to action for us to recognize the patterns of our past that reverberate in our present.

Final Thoughts

As we ponder this story, we must confront the societal trends and issues it brings to light.

Prejudice, scapegoating, and violence against marginalized groups are not relics of a medieval past; they are challenges we continue to face today.

The story of Basel acts as a mirror, reflecting the flaws and issues in our own societies.

It urges us to look beyond the simplistic divisions of us versus them, to understand the complex diversity of human nature, and to strive for a world where empathy and understanding triumph over fear and ignorance.

In the end, the history of January 9th, 1349, in Basel is a stark reminder of our shared humanity and the dangers of allowing fear and prejudice to dictate our actions.

Events like these are a call to embrace the diversity of the human experience and to learn from the lessons of our past to build a more inclusive, compassionate future.